Meditation is Simple but not Easy

Meditation as a Catalyst for Change, Part III

There are many within the meditation community who have blazed a path of integrity outside the consumerist paradigm. The Vipassana meditation centers around the world, for example, provide ten-day (and longer) courses to tens of thousands of people yearly—for free. Existing completely on donations, the meditation courses and room and vegetarian meals cost nothing. Nothing but one’s time and effort. Teachers donate their time, as do the volunteers who provide food, organization, and support.

These meditators volunteer ten and more days at a time because they compassionately wish to share the benefits of meditation. The students are well represented by the full spectrum of gender, socio-economic class, ethnicity, and religion. There is no cult or religion, no guru, no coercion of donation or service. In a world of expensive ashrams, New Age resorts, and paid spirituality, the Vipassana meditation centers serve as iconoclasts, as role models for a post-consumerist paradigm.

And so the leaders in the field wave us forward, exhorting us to meditate. Swami Muktananda said that as we meditate more “we become transformed.” “And, if we—you and I—are to further the evolution of mankind,” submits philosopher Ken Wilber, “and not just reap the benefit of past humanity’s struggles, if we are to contribute to evolution and not merely siphon it off, if we are to help the overcoming of our self-alienation from spirit and not merely perpetuate it, then meditation—or a similar and truly contemplative practice—becomes an absolute ethical imperative, a new categorical imperative.”[i]

Sri Nisgaddata Maharaj, a spiritual teacher of Nondualism, said, “You have to go within… From my standpoint love is the quality to be. Beingness is love… But just to sit there and listen will not do. You have to meditate.”[ii]

And Sri Dhammananda, considered the foremost Theravada Buddhist monk in Malaysia and Singapore said, “No one can attain… salvation without developing the mind through meditation.”[iii]

And not just an hour or two a week. The prescription requires a lot of meditation.[iv] S.N. Goenka suggests a ten-day course a year and two hours of meditation a day, as a minimum. And even then it will take years to perfect a harmonious life. “People underestimate the kind of effort that is required to transform oneself in a spiritual practice,” says the American Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield.[v]

Moreover, meditation is simple, but it is not easy. The Dalai Lama has said that “Some forms of meditation are very difficult… A close friend who had spent several years in a Chinese prison… told me that the meditation was actually harder than being a prisoner.”[vi]

Meditation is hard work, and it takes a long time to manifest its wonders. No wonder so relatively few people meditate daily, even with all its purported benefits. It is the same reason we don’t all train our bodies like decathletes, even though many of us may wish for the health and anatomical benefits. We are accustomed to quick fixes, pills and capsules, fast food, instant delivery, life broad-banded, what we want when we want it.

And now, when we want to transform ourselves for the betterment of the world, to weaken our ego traits and to access altruistic behaviors spontaneously and frequently, we find that it takes years of mental training. It has been found that to achieve mastery in any discipline, whether it is chess, hockey, or the violin, one must work tirelessly for years, undergoing, according to some, a magic ten-thousand hours of serious practice.[vii] The same has been claimed about meditation. “Expert” meditators have to log in their ten-thousand hours.[viii] Which comes to ten years of twenty-hour weeks, or twelve years using Goenka’s two-hours a day prescription. This require that meditation becomes a true priority in one’s life.

And because it takes such a sustained and intense practice to achieve the deep-lying results and to transmit them from master to student, there are relatively few committed aspirants and even fewer masters. For this reason alone, meditation is unlikely to be humanity’s answer to the punctuated jump in consciousness (and associated behaviors) we need to resolve our ecological predicament.

If its benefits are, as the meditation masters promise us, available to all, and if these benefits are sufficiently adaptive for our species, then it will likely become part of the human cultural repertoire some day in the future. But unlikely soon enough to avert the coming dieback or to inform our behaviors to compassionate and selfless action during the tough times ahead. Still, eventually, sometime in the long future of our species, our distant descendants will make it part of their daily lives.

Here again, we find ourselves in a familiar dilemma. Meditation seems to be one of the few tried and true ways that a person can achieve inner transformation and change the internal paradigm from one of selfishness to selflessness, a useful ingredient if we are to voluntarily downsize our big First World lifestyles.[ix] That is, we may actually have the solution to the human predicament. Like a set of instruction manuals, the various meditation techniques are readily available to us. We simply need to open one up and practice. But we won’t. Half of us don’t know that the manual is sitting there on the shelf, and the other half won’t commit ourselves to putting in the necessary work.

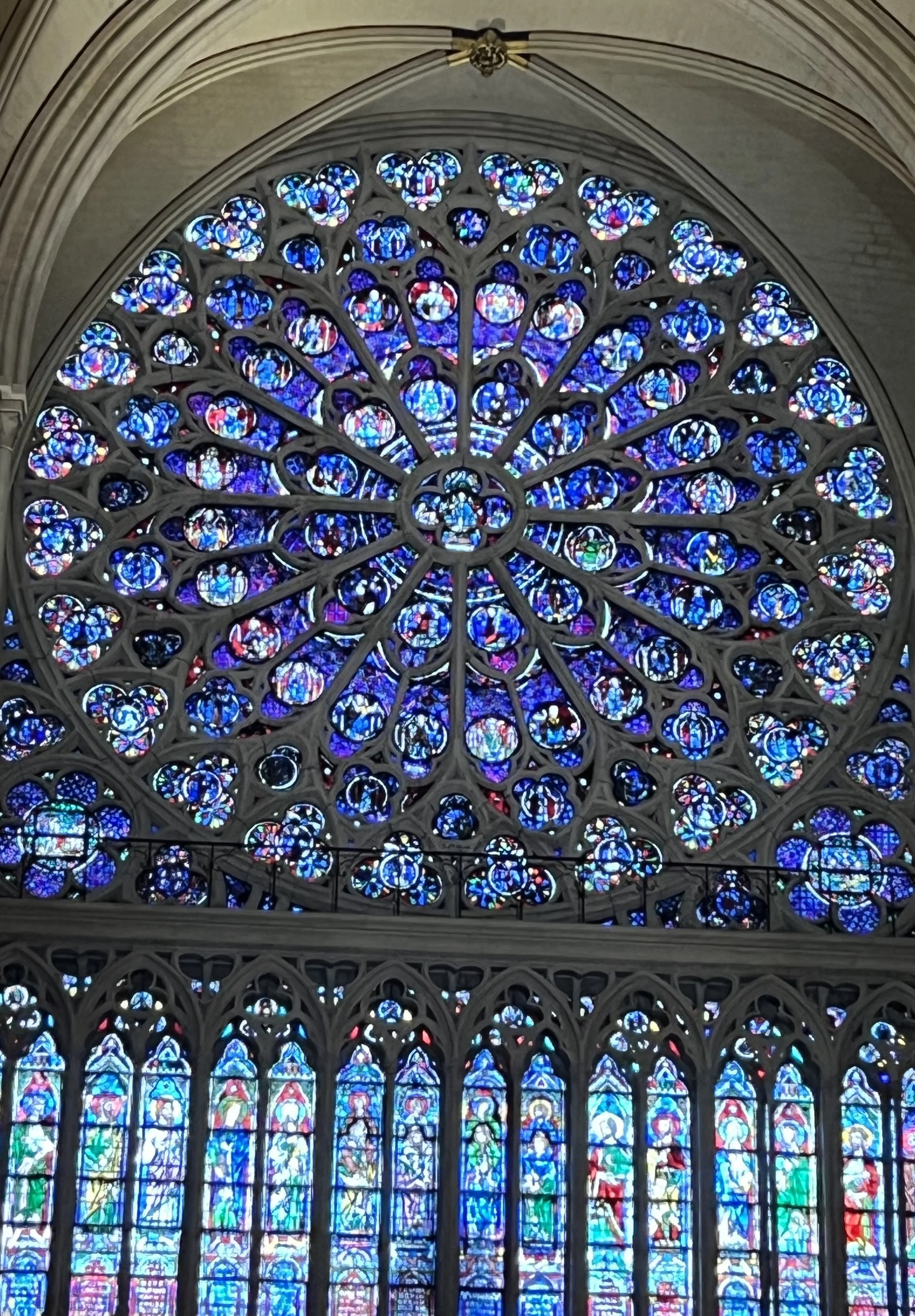

And so comes a warning about a life without meditation from social philosopher and poet William Thompson: “Nothing less than truth, goodness, and a Buddhist universal compassion are going to get us through the transition from industrialization to planetization. Our level of consciousness has now become the biggest obstruction to the continuity of human existence. We have made normalcy nonviable, so we have opted for an “up or out’ scenario in cultural evolution. We either shift upward to a new culture of a higher spirituality to turn our electronic technologies into cathedrals of light, or we slide downward to darkness and entropy in a war of each against all.”[x]

[i] Wilber (1981:319-332). Wilber, K. (1981:319-332) Up from Eden: A Transpersonal View of Human Evolution. Shambhala, Boulder, CO.

[ii] Nisgaddata Maharaj (1982:19,32,40). Seeds of Consciousness, The Acorn Press, Durham, NC.

[iii] Dhammananda (2002:278-279). What Buddhists Believe. Buddhist Missionary Society, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

[iv] Brinkerhoff, M.B., and Jacob, J.C. (1999) Mindfulness and Quasi-Religious Meaning Systems: An Empirical Exploration within the Context of Ecological Sustainability and Deep Ecology. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion; 38(4): 524-542.

[v] Kornfield in Forte, R. (2000) Psychedelic Experience and Spiritual Practice: An Interview with Jack Kornfield, pp. 119-135, in Forte, R. (Editor) Entheogens and the Future of Religion. Council on Spiritual Practices, San Francisco, CA.

Transcendental Meditation (often shortened to “TM”) asks much less of the beginner—two twenty minutes sessions a day. It has become a popular form of meditation in the United States, partly due to the efforts and funding of the David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and World Peace (Hoffman, 2013).

[vi] Kabat-Zinn, J., and Davidson, R.J. (Editors) (2011:84) The Mind’s Own Physician: A Scientific Dialogue with the Dalai Lama on the Healing Power of Meditation. New Harbinger Publications, Inc., Oakland, CA.

[vii] Ross, P.E. (2006, August) The Expert Mind. Scientific American: 64-71.

And famously: Gladwell, M. (2008:35-68) Outliers: The Story of Success. Back Bay Books, Little, Brown and Company, New York.

[viii] Lutz et al. (2008).

[ix] Mystical experiences have also been attributed to, among other practices, psychedelics, breathing exercises (such as pranayama and holotropic breathwork), chanting, singing, dancing (e.g., whirling dervish), fasting, praying, drumming, and sensory deprivation, however none have a well-established record of psycho-spiritual transformation.

[x] Thompson, W.I. (1998:10) Coming Into Being: Artifacts and Texts in the Evolution of Consciousness. St. Martin’s Press, Griffin, New York.