Humanity’s Long Strange Trip with Psychedelics

Psychedelics as Catalysts for Change, Part I of V

The word psychedelic, from its Greek roots, means mind or soul manifesting.[i] What takes decades to cultivate through disciplined meditation practice can arrive in mere hours with psychedelics, or, in the case of DMT, minutes.[ii] They have been so effective in generating mystical experiences that some people refer to them as “entheogens,” literally generating the god within.

Chemically, psychedelics tend to fall into two main groups: the tryptamines which include LSD, psilocybin, and DMT (the main psychoactive component in ayahuasca), and the phenethylamines such as mescaline.[iii] Although the precise phenomenological (internal, subjective) experience of each specific psychedelic substance differs, they have in common the ability to induce states of consciousness that are, according to researchers, “indistinguishable from classically described mystical experiences.”

To this end, psychedelics are the most powerful chemical agents known. And as the scientists Roland Griffiths and Charles Grob wrote, “Mystical experiences can bring about a profound and enduring sense of the interconnectedness of all people and things—a perspective that underlies the ethical teachings of the world’s religious and spiritual traditions.” Because it may be this very depth of awareness that stands between us and the abyss of ecocide and evolutionary suicide—we must earnestly consider the role of psychedelics as essential tools of our survival.

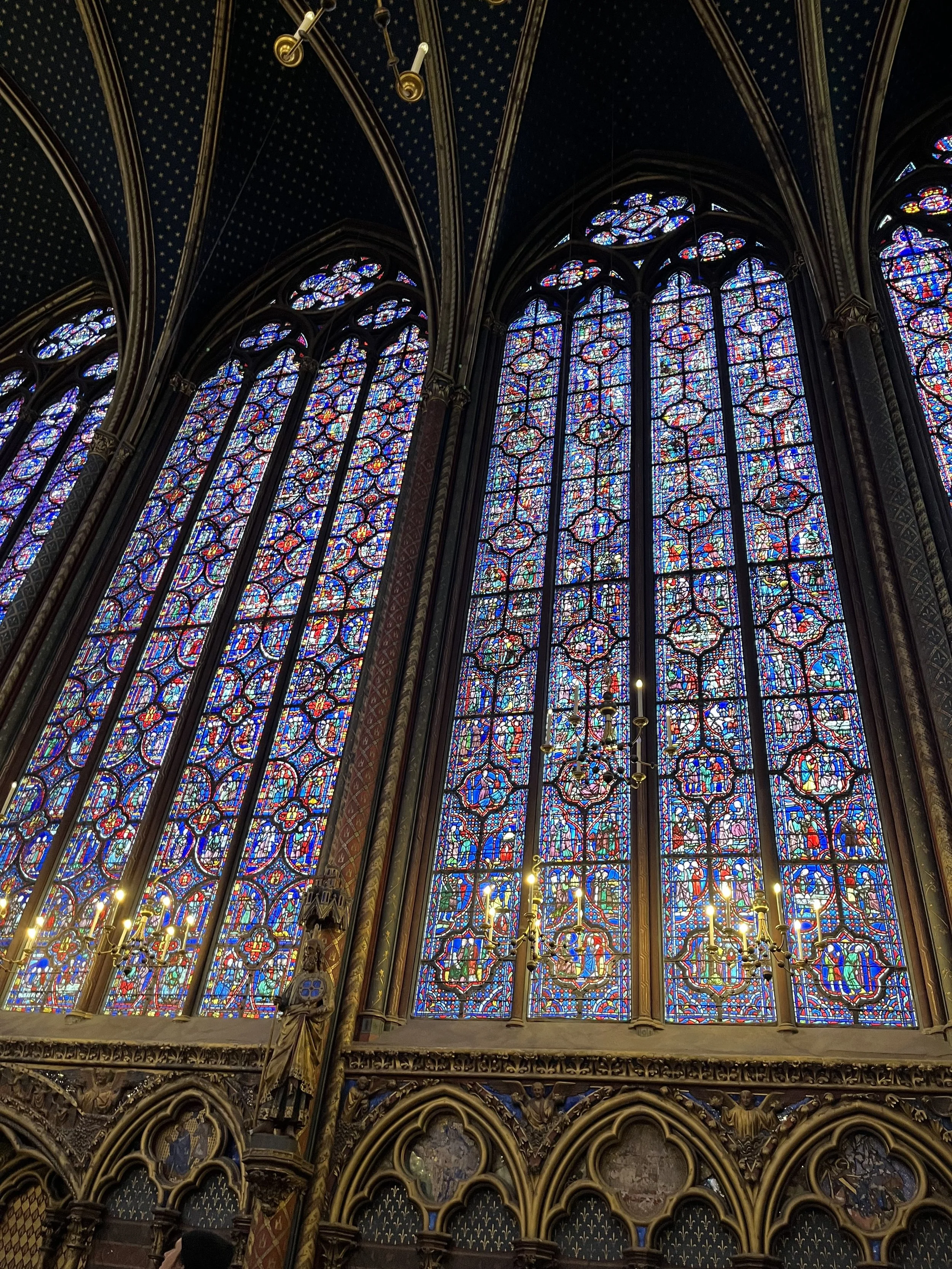

The religious and mystical use of psychedelic plants and fungi probably preceded the known meditation schools by thousands of years. Literary texts and archaeological artifacts indicate their use in religious, ceremonial, and healing contexts across the entire inhabited world, from ancient India and Persia to Africa and the Americas. The substance was carefully prepared from the flora or fungi by an adept, often the shaman, and administered in a ritualized, ceremonial setting. Group values were transmitted, and rites of passage were performed. Because of their mystical powers, the plants and mushrooms were considered divine and their use sacramental.

However, the path of cultural evolution has been neither linear nor everywhere simultaneous. Social complexity and the material benefits of civilization have come at a psycho-spiritual expense—a growing alienation from nature, community, and self. Our relationship to each of these has dulled, as if alcohol and opium had slowly infused into the lifeblood of Western civilization.

During these same millennia, the use of psychedelics for religious and mystical purposes faded in most of the world. Perhaps, as some believe, the religious institutions and other elite discouraged the use of psychedelics in the same ways that they discouraged most other indigenous mystical practices, especially those that promoted individual mystical experiences that were outside of the authority of the established religion.

This usurpation of sacred plants by the elite has been recorded among the Inca, Aztec, and Mayan civilizations and is hypothesized to have occurred in ancient Greek and Roman societies, as well. As societies became stratified, the use of sacred plants for mystical purposes were increasingly “withheld from widespread use,” and “hierarchies intercede[d] between man and the supernatural.”[iv]

Favoring this idea is that sanctioned ceremonial use of psychedelics thrives only at the margins of Civilization—ayahuasca, cimora and various Datura species in the Amazon, ibogan in Gabon, and peyote among some North American Indians. Peyote had likely spread from North Central Mexico where the Huichol and other groups had been using it religiously, ceremonially, and medically since at least the 2nd century C.E.

By the late 19th century, U.S. governmental authorities and Christian missionaries had successfully suppressed its use among most North American Indians. Most, but not all. The traditions were maintained. According to UCLA professor Charles Grob, “Only by going deeply underground and maintaining their world view and shamanic practices in secret from the dominant Euro-American culture, has this knowledge survived.”

Today, with the protection of two Supreme Court Cases, about three hundred thousand native North Americans regularly and legally ingest psychedelics in the form of mescaline “as a religious sacrament during all-night prayer ceremonies in the Native American Church.” And the use of ayahuasca by Brazilian syncretic religions has received legal sanction in several Latin American countries and beyond.

It has only been since the mid-twentieth century that the European-American West has been slowly in fits-and-starts reclaiming the lost knowledge. About the same time that the Eastern mystics were arriving in California with their message of meditation and happiness in this world, chemist Albert Hoffman was synthesizing LSD in the Sandoz labs in Switzerland (1943), anthropologist Wasson was discovering the “magic mushroom” in Mexico (1957), and luminary Aldous Huxley was connecting the psychedelic experience to the perennial mystical traditions (1954).

Then, during the 1960s and 70s, as if in a Dionysian frenzy, the rediscovery of the magical qualities of psychedelics exploded on American and European college campuses and in the inner cities and wealthy suburban neighborhoods. (Continued in Part II).

[i] According to Nichols (2004), “Hallucinogen is now … the most common designation in the scientific literature, although it is an inaccurate descriptor of the actual effects of these drugs. In the lay press, the term psychedelic is still the most popular…” - Nichols, D.E. (2004) Hallucinogens. Pharmacology and Therapeutics; 101: 131-81.

[ii] Actually, what they promise are satori experiences, which is a brief insight or realization into the nature of reality, whereas enlightenment is considered a lasting experience.

[iii] LSD has also been placed in other chemical families.

[iv] De Rios, D.M., and Smith, D.E. (1976) Using or Abusing? An Anthropological Approach to the Study of Psychoactive Drugs. J. Psychedelic Drugs; 8: 263-266.